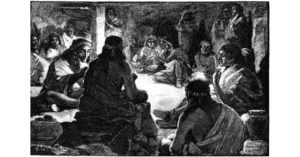

Storytelling has been around since language was invented. And for thousands of years, until written language came along, storytelling could only be oral.

We have all heard great oral stories. Everyone has a friend or two whom they think of as an excellent, if not a near-professional, storyteller. But only a handful have what we now consider to be the “gift” of entertaining oral storytelling, the ability to pull the listener into the story and seize their sensibility.

Then, no matter how good the telling of it, once the story is told – once it is over – the story is gone, except for the memory. And of course, then the story is subject to the whims of our minds, in particular that most dreaded foible of all: forgetting.

That’s a rather obvious reason to write stories down. To preserve them in an unchanging form. But what about the quality of the story?

In oral storytelling there is first and foremost the story itself. The characters and their development. The scenes and settings where they operate. And the actions they take – the plots, or story-lines, if you’d rather. These are the content of the story. But beyond the story content, in oral stories there is the storytelling as well. And we all know that someone good at storytelling can make even a simple story sparkle. Unfortunately on the other side of the coin, a poor oral storyteller can turn a even a gobsmacking saga into a droning sermon.

In my experience of writing the stories told by hospice patients, I have come to this conclusion: There are considerably more good stories than there are entertaining storytellers. I’m sure that there are many reasons for this. That entertainment itself is now globe-straddling industry with professional practitioners, is to name but one.

So consider a simple-sounding proposition: When you write someone’s story, anyone’s story, you become the entertainer – the storyteller. It is up to you to capture and keep the audience. It is up to you to compel them to read the next line, the next paragraph, the next page. Sure there has to be a good story, but the there has to be a good storyteller as well – whether the story is oral or written.

As writers we all know good stories, quality stories, when we hear them, even if the teller is not so entertaining in telling them. But once we write that story out, we become the teller, and it is up to us to make the quality of the telling commensurate with the quality of the story content. To be compelling, to be entertaining, the story must exhibit both.

If you want to write to express your own inventiveness in creating characters, scenes and plots that is great. That is inventiveness of story content. But if inventiveness of writing, of storytelling, is what you most enjoy, then consider creatively writing other people’s story content. I assure you, once you go looking for sensational stories that were actually lived, you will find them in uncountable numbers. Everybody has at least a few.

And once you capture and creatively write those fantastic stories, in a very real and deeply rewarding sense, the finished product – the written story – will be every bit as much yours as your writing partner’s.